After receiving such a positive response to my recent blog post about John Frost, a leading Chartist transported during the 1800s, I decided to continue going down this path for my research blog and stumbled across William Cuffay. Black, disabled and working class in 19th century Britain yet a leading figure in the Chartist movement, in particular the 1848 uprising. Cuffay was transported for life to Van Diemen’s Land, what is now known as Tasmania, where he continued his political activism, unlike most other Chartists transported. Described by Norbert J. Gossman in his 1983 William Cuffay: London’s Black Chartist as ‘the true outsider, black, physically deformed and given to “demagoguery”’, I couldn’t understand why there was so little information out there about such a remarkable and unusual figure, especially in terms of his later life after Chartism and transportation (1983, 64). And so, my research began!

© Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, London

Born in 1787 or 1788 (records vary), the son of a former St. Kitts slave, Cuffay trained as a tailor. What then led to this unlikely figure becoming so politically active? Dorothy Thompson, in The Early Chartists suggests that the ‘tailors strike of 1834 probably contributed to his radicalisation’ and I believe this to be true as the strike, which saw 20,000 men partake in protest against the transportation of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, was unsuccessful and its collapse led to unemployment for Cuffay and many other working men, who then became politicised (1971, 9). This is shown by an article in The Northern Star, the leading Chartist newspaper. The article shows nominations to the Chartist General Council in 1841 – tailor is one of the most popular occupations of those nominated, showing how disillusionment with working conditions led to politicisation. 1841 is also the year we begin to see Cuffay’s name in newspaper articles relating to Chartist activity. By 1848 he was an executive of the National Charter Association.

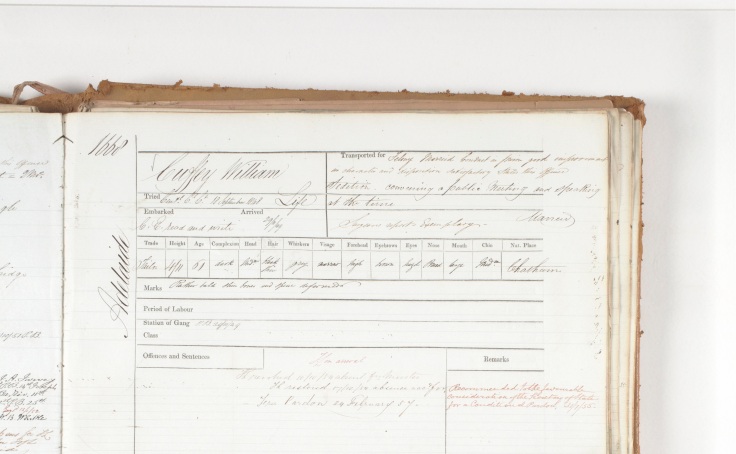

Cuffay’s involvement in Chartism then culminated in the infamous events of 1848 – he was one of the leading organisers of the Kennington Common Demonstration and the presentation of the third national Charter. He was tried on 18th September 1848 and sentenced to transportation for life for what is described in his Old Bailey trial proceedings as his attempt ‘to levy war against the Queen’. He was transported to Tasmania on the Adelaide ship, departing on 17th August 1849 and arriving on 29th November, according to his conduct record, which can be found in the digital Tasmanian Library archives.

After the announcement of Cuffay’s arrest, money had been raised by Chartist subscribers to support his wife, Mary Ann. An example of this can be seen in The Northern Star article ‘Shoemakers’ Exhibition for the Chartist Prisoners’, which explains how ‘money was collected by the late exhibition of prize boots and shoes’ and distributed between the families of those imprisoned, with Mary Ann receiving 7 shillings. After Cuffay’s transportation, Mary Ann eventually joined him in Tasmania, arriving on 27th April 1853 on the Panama ship. She was 60 years old at the time. This is also noted as a remark on William Cuffay’s convict record stating that he applied to bring out family.

How this was achieved however can be disputed. Whilst Malcolm Chase, in his ‘Chartism’s Black Activist’ article for History Today, states that ‘4 years into his transportation Mary his wife was able to join him thanks to Chartist subscribers funding’, newspapers from the time suggest otherwise (2007, 22). Reynold’s Newspaper, on 7th November 1852, explains how ‘Mrs Cuffay, wife of Mr W. Cuffay, the exiled Chartist, is joining her husband in Australia. Government defrays one-half of her passage, and the union workhouse at Chatham, of which she is an inmate, the remainder.’ Whilst the latter explanation seems more of a reliable source than Chase’s claim, both establish something about Cuffay – that he was a prominent and popular figure to have had either enough support from his fellow Chartists to raise money to reunite him and his wife or for the government to help financially support their reuniting.

Something that really stood out to me about Cuffay was his determination to continue his radical political activism after being transported and after receiving a free pardon. He was involved in the successful anti-transportation campaign – the last convict ship arrived in May 1853, not long after Mary Ann’s arrival. In the chapter ‘Changing Empire: William Cuffay’ in Peter Fryer’s 1984 book Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain, Fryer explains how upon arrival in Tasmania, Cuffay ‘was active in the successful agitation for the amendment of the colony’s Masters and Servants Act’. The act stated that workers could be treated as criminals and punished by hard labour, sentenced to the treadmill and imprisoned for breaches of contract such as leaving their job without permission. Although not completely removed in Cuffay’s life time, the act was amended in 1856 and the Mercury’s obituary for Cuffay states how he ‘contributed in a great degree to the settlement of the Masters’ and Servants’ question on a satisfactory basis’ anchoring how his reforming zeal made an impact on not just British law with Chartism but on Tasmanian law too.

According to his conduct record, he was granted a free pardon from the Queen on 24th February 1857 yet he remained in Tasmania up until his death, politically active right through his 70s and into his 80s, making various speeches and appearances and writing political pieces. Also, upon arrival in Tasmania, Cuffay didn’t even have to wait for a week to receive a ticket of leave, being granted it on 3rd December 1849. This almost immediate granting left Cuffay free to practice his trade and get on with work and life, ‘he was employed as a tailor, until he could no longer work because of failing health’ (58), explains Ron Ramdin in his 1999 Reimaging Britain five hundred years of Black and Asian history. We can see this from one of his last public appearances, when on the platform of a meeting at the Theatre Royal, he explained: ‘fellow-slaves, I’m old, I’m poor, I’m out of work, and I’m in debt’ which shows how despite being such a politically prominent figure, often wrote about in newspapers both in the UK and Australia, Cuffay sadly fell victim to poverty – the poverty which he had campaigned against, providing a voice for working class men and their rights not in just one country, but in two (The Mercury, 4th August 1870).

In October of 1869, shortly after Mary Ann’s death, William Cuffay was admitted to what papers such as the Hamilton Spectator described as the “Brickfields pauper establishment” (the Brickfields Invalid Depot) – a workhouse where he eventually died on 29th July 1870 at the age of 82. On his death certificate he is described as a pauper. A sad state of affairs, it shocks me what became of such a pioneering and famous figure in his final years, as the newspaper put it: ‘in his old age poverty overtook him, and he fills a pauper’s grave.’

One other aspect of Cuffay’s life that really interests me is the media’s representation of him. Martin Hoyle in his fantastic book William Cuffay: The Life & Times of a Chartist Leader perhaps summarises this best: ‘as well as being loved and respected by his fellow Chartists, Cuffay was feared and reviled by the Establishment.’ (2013, 248) We can really see this in the contrasting ways that Cuffay was portrayed in the Chartist press such as the Northern Star and what we may today call the Establishment media, for example in The Times and in Punch – a satirical magazine.

Racism played a key role in the media’s portrayal of Cuffay, with The Times referring to him as ‘half a n*gger’ in 1848 and Punch magazine lampooning him with cartoons such as the one below and satirical poems including one by William Makepeace Thackeray titled The Three Christmas Waits. In the poem the colour of his skin is repeatedly drawn attention to and his slave ancestry is mocked. As Malcolm Chase said in his ‘Chartism’s black activist’ article for History Today: ‘Even by the standards of the time the portrayal of Cuffay was savage’- for someone to carry out such prolific political and reforming work yet their race be the main thing focused on is not just a reflection of societal attitudes during the period but also a reflection of those individuals in positions of power at the time (2007, 20). Interestingly, I also failed to find any detailed writing from historians about Cuffay from before 1983, aside from an 1894 book written by Robert Gammage, who was both a prominent Chartist himself and the first real Chartist historian. The book is titled History of the Chartist Movement 1837-1854 and I came across it through Mark Crail’s Chartist Ancestors website. Apart from that one anomaly though, it seems up until 1983 Cuffay was omitted from history by many academic writers, which sadly does not surprise me.

Yet the Chartist press and other working class publications portray Cuffay in the way that he should be remembered today: a working class hero. One article in The Star and National Trades’ Journal tells how Cuffay ‘deserves to be separately eulogised’, his ‘memory kept green and fresh in the hearts of all’ and hundreds of Northern Star articles mention him too, all that I have come across praise and support him with no mention of his skin colour or disability.

‘We owe a lot to William Cuffay. A man who survived disability, poverty, bereavement, unemployment, ridicule, racism, imprisonment and transportation’, concludes Martin Hoyles in his William Cuffay: The Life & Times of a Chartist Leader and perhaps there is no better way to end any discussion of him than without highlighting this (2013, 253).

Despite all the disadvantages and difficulties Cuffay was faced with, he was an important, pioneering figure who campaigned tirelessly and selflessly for social and political reform in not just one but two countries. Chartism was the first political mass movement driven by the working classes. He stood at the forefront of it, which as a black, disabled man in 19th century Britain must not have been easy and if the Punch and The Times articles I have unearthed are anything to go by, it must have been extremely tough for him. Although all the aims of Chartism were not achieved in Cuffay’s lifetime, they have now been achieved and his contribution to that must be recognised and celebrated alongside his contribution to Tasmanian reforms. A remarkable, inspiring, unique individual, who kept on trying until the day that he died, a film about Cuffay’s life would be a box office hit for certain and why one has not already been made, baffles me!

Bibliography:

Primary sources:

(in order of appearance)

Founders and Survivors. William Cuffay’s Life History [online]. Available at: http://www.foundersandsurvivors.org/pubsearch/convict/chain/ai16316 [Accessed 13th January 2019]

The Digital Panopticon. William Cuffei b. 1788, Life Archive ID obpdef3-2181-18480918, Version 1.1. [online] Available at: https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef3-2181-18480918 [Accessed 13th January 2019]

Libraries Tasmania Archives. Cuffey, William. Conduct Record. [online] Available at: https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=william&qu=cuffay [Accessed 13th January 2019]

Parssinen, T., & Prothero, I. (1977). The London Tailors’ Strike of 1834 and the Collapse of the Grand National Consolidated Trades’ Union: A Police Spy’s Report. International Review of Social History, 22.1, pp.65-107.

The Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser (1841) Nominations to the General Council. Issue 178. British Library Newspapers, Part I: 1800-1900. [online], 10 April 1841. Available at: http://find.galegroup.com/bncn/ [Accessed 13th January 2019]

Trial of William Lacey, Thomas Fay, William Cuffei, 18th September 1848, Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Available at: http://www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0 [Accessed 13th January 2019]

The Northern Star and National Trades’ Journal (1849) Shoemakers’ Exhibition for the Chartist Prisoners. Issue 620. British Library Newspapers, Part I: 1800-1900. [online], 8th September 1849. Available at: http://find.galegroup.com/bncn/ [Accessed 13th January 2019]

Libraries Tasmania Archives. Cuffy, Mary. Arrivals Record. [online] Available at: https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=NI_SHIP_FACET%3Dpanama&rw=48&st=TL&isd=true [Accessed 13th January 2019]

Reynolds’s Newspaper (1852). Meetings and Democratic Intelligence. British Newspaper Archive. [online], 7th November 1852. Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/ [Accessed 13th January 2019]

The Mercury (1870). Death of a Celebrity. National Library of Australia [online], 4th August 1870. Available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/8869203 [Accessed 13th January 2019]

Hamilton Spectator (1870), Across the Straits, our Tasmanian letter [online], 24th August 1870. Available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/196307001 [Accessed 24th August 1870]

Libraries Tasmania Archives. Cuffy, William. Death Record. [online] Available at: https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=william&qu=cuffey [Accessed 13th January 2019]

The Times (1848), Central Criminal Court. The Times Digital Archive. [online], September 29th 1848. Available at: http://gdc.galegroup.com/gdc/artemis/?p=TTDA&u=livjm [Accessed 13th January 2019]

Thackeray, William Makepeace. (1848) Three Christmas Waits. London: Punch Magazine. Available at: https://m.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/three-christmas-waits-0 [Accessed 13th January 2019]

The Star and National Trades’ Journal (1852) Amnesty to all political exiles. British Library Newspapers Part I: 1800-1900. [online], 20th March 1852. Available at: http://find.galegroup.com/bncn/ [Accessed 13th January 2019]

Images:

William Cuffay drawn in his Cell in Newgate by William Paul Dowling (1848), National Portrait Gallery, London https://www.npg.org.uk/learning/digital/history/abolition-of-slavery/william-cuffay

William Cuffay’s Convict Record. Tasmanian Libraries Archive. https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=william&qu=cuffay

Image of William Cuffay in Reynolds’s Political Instructor magazine https://www.wcml.org.uk/our-collections/activists/william-cuffay/

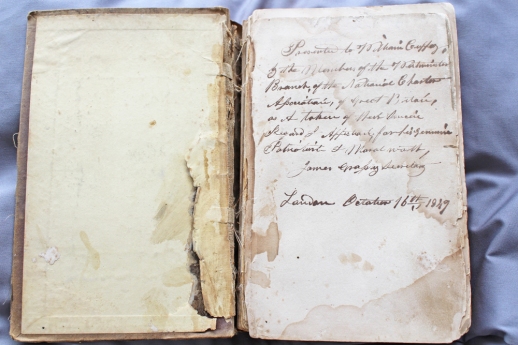

William Cuffay’s book, People’s History Museum. https://phmmcr.wordpress.com/2014/06/06/chartist-leader-william-cuffays-book-donated-to-peoples-history-museum/

The Political Life of Cornelius Cuffey, Esq., Patriot, &c, &c. https://cuffay.blogspot.com/2011/04/punch.html

Secondary sources:

Chase, Malcolm. (2007). Chartism’s black activist. History Today, 57.10, 2007. pp.20-23. p.22

Fryer, Peter. (1984) Changing Empire: William Cuffay. Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. London; New York: Pluto Press. Pp.237-246.

Gossman, N. (1983). William Cuffay: London’s Black Chartist. Phylon, 44.1, pp.56-65

Hoyles, Martin (2013). William Cuffay: The Life & Times of a Chartist Leader. Hertfordshire: Hansib Publications Ltd.

Ramdin, Ron. (1999). Reimaging Britain five hundred years of Black and Asian history. London; Sterling, Va: Pluto Press.

Thompson, D. (1971) The Early Chartists. South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press.

Leave a comment