When reading Oliver Twist, I was intrigued by the language used by characters such as the Artful Dodger. It was a distinct type of slang; a few of the terms I am familiar with and hear used today, but most of the words left me wondering about what they could mean. I decided to look into this and found that the type of criminal dialect Dickens employs in Oliver Twist was widely used within the 19th century underworld.

The language, or rather slang, used by the likes of the Artful Dodger and Bill Sikes, was known as “flash“, a term coined by James Hardy Vaux a British convict transported thrice to Australia. He defined Flash as ‘the cant language used by the family. To speak good flash is to be well versed in cant terms’ in his A Vocabulary of the Flash Language which featured in his book Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux first published in 1819. The book is regarded as both the first full length autobiography and the first dictionary written in Australia.

A particular exchange between the Artful Dodger and Oliver Twist, found in chapter 8 of the novel stood out to me:

‘Hullo, my covey! What’s the row?’ said this strange young gentleman to Oliver.

‘I am very hungry and tired,’ replied Oliver: the tears standing in his eyes as he spoke. ‘I have walked a long way. I have been walking these seven days.’

‘Walking for sivin days!’ said the young gentleman. ‘Oh, I see. Beak’s order, eh? But,’ he added, noticing Oliver’s look of surprise, ‘I suppose you don’t know what a beak is, my flash com-pan-i-on.’

Oliver mildly replied, that he had always heard a bird’s mouth described by the term in question.

‘My eyes, how green!’ exclaimed the young gentleman. ‘Why, a beak’s a madgst’rate; and when you walk by a beak’s order, it’s not straight forerd, but always agoing up, and niver a coming down agin. Was you never on the mill?’

‘What mill?’ inquired Oliver.

‘What mill! Why, THE mill — the mill as takes up so little room that it’ll work inside a Stone Jug; and always goes better when the wind’s low with people, than when it’s high; acos then they can’t get workmen. But come,’ said the young gentleman; ‘you want grub, and you shall have it. I’m at low-water-mark myself — only one bob and a magpie; but, as far as it goes, I’ll fork out and stump. Up with you on your pins. There! Now then! Morrice!’

As you can see, there are some words in the extract that would be unfamiliar to a modern day reader. Here is a “translation” of what they mean, collated using Hardy Vaux’s guide and Green’s Dictionary of Slang:

Covey: fellow

Row: problem/disturbance

Beak: magistrate

Flash: the criminal

Green: innocent

Mill: to sentence the treadmill, as in to imprison

Stone jug: prison

Grub: food

Bob: a shilling

Magpie: a halfpenny

Morrice: come on!

But, why do the criminal characters use this “flash language”? Well, the above extract is from Oliver’s first encounter with the Artful Dodger and it seems that as Oliver is on the streets begging, the Artful Dodger assumes he is someone who would understand criminal lingo. When the Artful Dodger realises Oliver does not understand his criminal slang, he calls him ‘green’ (meaning innocent). It is this discovery that the Artful Dodger uses to his advantage – rather than moving on from Oliver to someone who understands his slang, he seizes an opportunity to prey on Oliver’s innocence and recruit him as a member of his pickpocketing gang!

By calling Oliver ‘my covey’ and ‘my flash com-pan-ion’, he straight away establishes a feeling of community and friendship, the possessive pronoun ‘my’ creating a sense of familiarity and acception. This shows how the Artful Dodger uses “flash language” to groom Oliver to join in with his pickpocketing antics.

Interestingly, Hardy Vaux defines “flash language” as ‘the cant language’ and ‘cant’ is defined as ‘the jargon of a group, often employed to exclude or mislead people outside the group’.

This shows another reason for the use of criminal slang: to create a separation between the world of law and order and the criminal underworld. It is unlikely that words such as ‘stone jug’ for prison and ‘beak’ for magistrate would be understood by a law-abiding citizen, so they provide a good disguise for discussing criminal pursuits.

I decided to carry out one final piece of research involving “flash language” and that was to see if any of the words in the above extract are still used today. Whilst ‘grub’ and ‘bob’ definitely are – I even occasionally use them myself, the majority were nowhere to be found in the digital, modern day version of Hardy Vaux’s flash dictionary a.k.a urbandictionary.com! And, those that were on there had very different meanings to the ones understood in the 19th century underworld!

Bibliography:

Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux and A Vocabulary of the Flash Language: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Memoirs_of_James_Hardy_Vaux/Vocabulary

Information about James Hardy Vaux: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Hardy_Vaux

Green’s Dictionary of Slang: https://greensdictofslang.com/search/basic?q=covey

Online version of Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens: http://www.online-literature.com/dickens/olivertwist/

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Wordsworth Editions Limited. Hertfordshire. 2000.

Urban Dictionary: https://www.urbandictionary.com/

Information about “cant language”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cant_%28language%2

Image 1: https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/convict-sydney/james-hardy-vaux

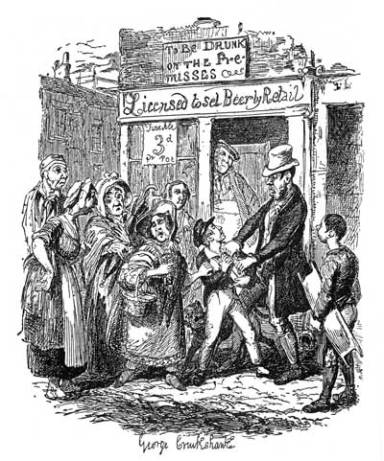

Image 2/Featured image: https://charlesdickenspage.com/illustrations-twist.html

Leave a comment